Evidence-Based Practice, ABA, and a Handy Checklist!

Of Course, You Use Evidence-Based Practice (EBP)! Doesn't Everyone?

Every day, ABA researchers validate new assessments and behavior change procedures for improving human behavior in clinical practice. Have you ever wondered when these new developments become "evidence-based?" Wait! ABA has been supported by rigorous empirical research for over 50 years, so isn't all ABA evidence-based? As it turns out, it depends on your definition of EBP and involves much more than just great science.

In the many different settings in which ABA is practiced, a considerable number of variables contribute to practitioner decision making including appeals to philosophy or authority (e.g., because Skinner said so!), marketing, insurance companies, changes in client behavior, anecdotes or testimonials, and the research-to-practice gap (Slocum et al., 2014).

Evidence-Based Practice and the Research-to-Practice Gap

In the 1960s, recognition of the research-to-practice gap in medicine was addressed by the development of evidence-based practice (EBP) standards. Later, other disciplines such as clinical psychology and special education followed suit.

For example, several major professional organizations (e.g., What Works Clearinghouse) have proposed standards for EBP in education, which use the term “practice” to refer to an empirically supported treatment, and generally, consider randomly controlled trials as the gold standard for empirical evidence. And these standards are applied in systematic syntheses of the literature for the purpose of identifying EBP. However, one criticism of this approach questions the application of EBP standards that themselves have not been empirically validated (e.g., Cook, Dupuis, & Jitendra, 2015). And some critics have suggested that such an approach may place too many constraints on practitioner decision making when so-called EBP don’t correspond sufficiently to the specific clinical problem at hand, which may include the practitioner failing to use the best available evidence because (a) it has not been given the EBP stamp of approval or (b) because there are no studies relevant to the problem (Slocum et al., 2014).

Consistent with our strong tradition of beginning any analysis with a clear definition of the phenomenon of interest, the discussion of EBP in ABA has begun to carefully consider definitions of EBP and related terms. Specifically, behavior analysts have begun to discuss how to conceptualize EBP in ABA (Smith, 2013) with the goal of arriving at a definition that reflects the core professional tenets, philosophy, and science of ABA, and maximizes our positive impact on society at large (Slocum et al., 2014). Furthermore, adopting a definition of EBP in ABA with sufficient overlap with other disciplines may help facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration that better serves consumers of ABA (Gardner, Hungate, Heitzinger, Ewbank, & Rogel, 2014).

Towards a Definition of EBP in ABA

Towards that goal, Slocum et al (2014) defined EBP in ABA as, “A model of professional decision-making in which practitioners integrate the best available evidence with client values/context and clinical expertise in order to provide services for their clients.”

In this definition, unlike some other definitions of EBP (e.g., Smith, 2013), the concept of a practice refers not to any particular intervention or intervention package, but rather “professional behavior” or “the professional practice of behavior analysis” (Slocum et al., 2014). In a sense, this definition makes EBP observable, measurable, and within radical behaviorism establishes itself as a valid target of analysis in a science of behavior. Now let’s break it down.

Best Available Evidence

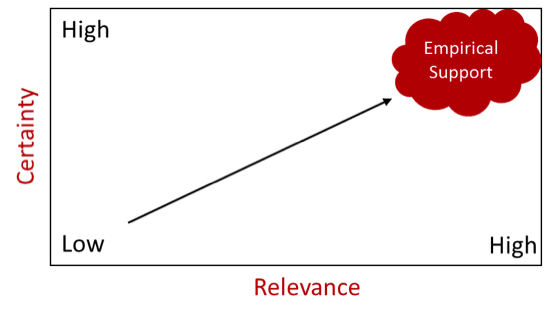

The concept of “best available evidence” is a central feature of EBP in ABA and is tied to (a) the BACB’s Professional and Ethical Compliance Code for Behavior Analysts®, and (b) a continuum of empirical support based on the certainty of the evidence and its relevance to a given clinical problem (Slocum, 2016). By evidence, we mean the support for selecting treatments, especially those for which there are no randomly controlled clinical trials or otherwise empirically supported treatment packages, making adjustments to current treatment, and utilizing progress monitoring data (Slocum, 2016). Low empirically supported treatments are low in relevance and evidential certainty, and high empirically supported treatments are high in relevance and evidential certainty (See Figure 1).

Evidence is relevant to the extent that a body of scientific literature corresponds to a clinical problem in terms of (a) client characteristics, (b) the behavior change procedures or assessments used in the study, (c) functions of behavior and expected outcomes of treatment, and (d) the environment in which the treatment is delivered (Slocum et al., 2014).

Based on the evidence, we can be more or less certain about whether a particular treatment was responsible for a change in behavior. Evidence has certainty to the extent that studies are methodologically rigorous (i.e., high quality) and findings are replicated (Slocum et al., 2014). With this approach, rather than relying only on the use of treatment packages or interventions that meet a set of EBP standards, the practitioner takes into consideration the full range of assessments and procedures and carefully considers their relative strengths and weaknesses. However, making use of the best available evidence doesn’t end with making use of the scientific literature to select treatments.

Figure 1. The relationship between certainty and relevance of scientific literature in the evidence-based practice of ABA. Better evidence is represented by increases in both dimensions (Adapted with permission from Slocum, 2016).

Figure 1. The relationship between certainty and relevance of scientific literature in the evidence-based practice of ABA. Better evidence is represented by increases in both dimensions (Adapted with permission from Slocum, 2016).

Progress monitoring provides the best available evidence of whether a particular treatment is actually working for a particular client (Slocum et al., 2014). As displayed in Figure 2 below, when empirical support from the scientific literature lacks certainty and relevance, EBP in ABA includes an increased reliance on progress monitoring consisting of rigorous ongoing data collection through more frequent direct interactions with the client, contact with the variables that will determine treatment outcomes, and adjustments of the client’s treatment plan until their goals are met. It’s important to also note that the best available evidence doesn’t directly influence the behavior of the client. Rather, with any luck it will serve as a verbal stimulus that alters the professional practice of the behavior analyst (Slocum, 2016), thereby narrowing the research-to-practice gap.

Figure 2. The relationship between empirical support and progress monitoring in the evidence-based practice of ABA. The best available evidence is contacted by the practitioners through increases in both dimensions (Adapted with permission from Slocum, 2016).

Figure 2. The relationship between empirical support and progress monitoring in the evidence-based practice of ABA. The best available evidence is contacted by the practitioners through increases in both dimensions (Adapted with permission from Slocum, 2016).

Client Values and Context

The integration of client values and context includes consideration of the social validity of the treatment plan, outcomes, and goals as judged by stakeholders and individuals in contact with the treatment. It also includes integrating the values, preferences, and characteristics of caregivers and other intervention agents into the treatment plan by programming motivating operations, reinforcers, and punishers that sustain treatment plans with high fidelity (Slocum et al., 2014).

Clinical Expertise

Clinical expertise refers to, “the competence attained by practitioners through education, training, and experience that results in effective practice”, and is, “the means by which the best available evidence is applied to individual cases in all their complexity” (Slocum et al., 2014).

Here is the Checklist! How Evidence-Based is Your ABA practice?

To what extent do you utilize the best available evidence?

| 1. | I rely on scientific knowledge by referring to the scientific literature regularly | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 2. | I compare participant characteristics of relevant studies to my clients’ characteristics | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 3. | I consider functions of behavior and expected treatment outcomes for clients in relation to the literature | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 4. | I compare the environment in which relevant studies were conducted to my clients’ environments | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 5. | I am more likely to use treatments with a high degree of evidential certainty as indicated by scientific literature reviews (e.g., empirically supported treatment reviews, narrative reviews or best practice guides) | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 6. | When the research lacks relevance or certainty, my data collection and systematic treatment evaluation intensify | Yes No Not Sure |

To what extent do you include client values and context in treatment plans?

| 7. | I prioritize immediate and important changes in clients’ lives | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 8. | My treatment plans seem to be highly valued and judged appropriate | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 9. | My treatment plans tend to be adopted and supported by caregivers, staff, and other stakeholders | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 10. | My treatment plans are supported with adequate resources and align with behavior change agents’ motivating operations, reinforcers, and punishers (i.e., their values, skills, goals, and stressors) in a manner that enables and sustains treatment plans with high integrity. | Yes No Not Sure |

To what extent do you have the relevant clinical expertise?

| 11. | I have sufficient knowledge of the research literature applicable to the population I serve | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 12. | My work relies on the conceptual system of ABA | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 13. | The breadth and depth of my clinical and interpersonal skills are appropriately matched to the population I serve, including the use of easily understandable language while remaining conceptually systematic | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 14. | I integrate client values and context into all of my treatment plans, which involves including stakeholders (e.g., caregivers) in the decision-making process. | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 15. | I regularly recognize when meeting a clients’ needs requires consultation with another behavior analyst or other professional and I take appropriate action such as making a referral | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 16. | I demonstrate competent use of data-based decision making when designing, evaluating, and revising treatment plans | Yes No Not Sure | |

| 17. | I regularly attend conferences, seek additional coursework, attend workshops or local events, publish research (which may consist of clinical case studies), or engage in other relevant activities to maintain my professional development. | Yes No Not Sure |

Congratulations on taking a step towards assessing your practice in the context of the EBP of ABA! Could this concept of EBP in ABA change how you provide client services or supervision to supervisees? Could the checklist be used to assess EBP in ABA in your organization? Might you go digging in the literature to learn more?

Bryant C. Silbaugh, PhD, BCBA,LBA Bryant is a Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) working in the Austin, Texas area. He provides services to children and families, along with supervision to aspiring behavior analysts, through his private agency. Some of Bryant's interests include the mechanisms of operant variability and the treatment of pediatric feeding disorders in children with autism. He has published in multiple peer-reviewed scientific journals. These include Developmental Neurorehabilitation and the Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Bryant teaches courses in behavior analysis as an online co-instructor for Florida Tech. Bryant is a doctoral candidate at the University of Texas at Austin, in the Special Education Department with a concentration in Autism and Developmental Disabilities. Acknowledgment: We give special thanks to Timothy Slocum for his comments on an earlier draft of this blog entry.