Agency and Shaping

Shaping, or the differential reinforcement of successive approximations, is thought by many to be the most important tool in the behavior analyst’s toolbox. Shaping is usually thought of as something one human does to change the behavior of another living organism, most often to a human but also to a pet or a laboratory subject of the nonhuman persuasion. In such cases, the human is the agent of the shaping in that the human decides the conditions under which successive approximations do or do not merit reinforcement.

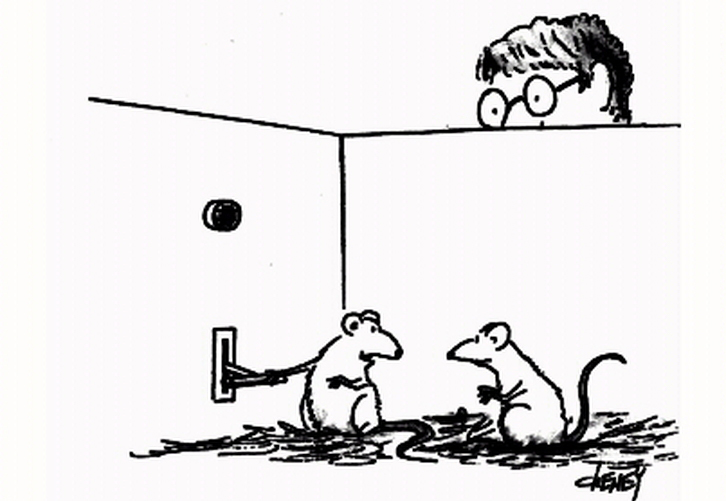

Must the agent—the provider of the reinforcers—of shaping be a human one? Certainly not. The agent doesn’t have to be a person. One need think no further than the famous cartoon of two rats in a Skinner box in which the one leaning against the lever says to his partner, “Boy, do we have this guy conditioned. Every time I press the bar down, he drops a pellet in.” Our pets are notorious for shaping our behavior in the same away, and my own laboratory animals have done an admirable job of shaping my scientific behavior!

In all of the above examples, the shaper is a living organism. But must the agent of shaping be sentient and living? Could the agent be a machine equipped with sensors for detecting approximations to the target response, an algorithm for detecting and reinforcing successively closer approximations to the target response, and a means for delivering reinforcers following the latter? Joseph Pear of the University of Manitoba in Canada was the first (as far as I know) to develop a workable computerized shaping system. His work was reported in the March 1987 issue of the Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. But, even here, it is really Joe’s ingenious engineering and programming that are behind the computer’s shaping skills, so agency still lurks in the background of this creative example of shaping.

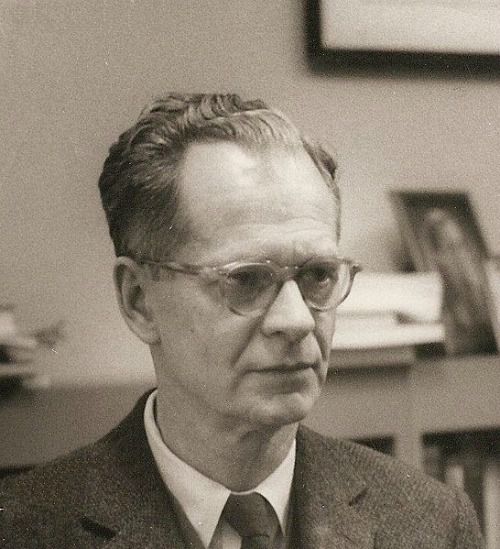

Take it a step further and step into situations where there is neither a living organism nor a computer lurking in the background in a Wizard-of-Oz–ish pulling of the strings to make reinforcement of successive approximations happen. Everyone has had the experience of trying to complete some complicated task in the absence of instructions or help from others only to fail on the first try. It often takes several tries before success happens. Once it does and the problem presents itself again, guess what? It is much easier to solve because of the previous what-might-be-called natural shaping that transpired earlier. The classic example of shaping in the absence of a human (or computer) algorithm operating to shape the response, what I will call natural shaping, is Skinner’s superstition experiment. In this experiment, he reported that pigeons engaged in idiosyncratic, stereotyped responses as a result of the adventitious reinforcement of such patterns. The reinforcement was simply an outcome of the accidental, temporal proximities between particular kinds of responses and reinforcement delivery. Whether the mechanism was really adventitious reinforcement remains controversial over 70 years after his original report.

The classic example of shaping in the absence of a human (or computer) algorithm operating to shape the response, what I will call natural shaping, is Skinner’s superstition experiment. In this experiment, he reported that pigeons engaged in idiosyncratic, stereotyped responses as a result of the adventitious reinforcement of such patterns. The reinforcement was simply an outcome of the accidental, temporal proximities between particular kinds of responses and reinforcement delivery. Whether the mechanism was really adventitious reinforcement remains controversial over 70 years after his original report.

In such cases of natural shaping, as described in the preceding two paragraphs, one could describe the environment itself as the agent, and that seems quite acceptable as long as we don’t throw intention into our equation. Skinner made the point long ago that behavior is selected by its consequences: the very essence of shaping. There is no shaper, no sentient agent, guiding and directing behavior, only the natural forces of any environment that operate on behavior so that when it happens certain consequences do or do not accrue. Shaping in these circumstances may be said to have an agent, but the agent is the natural circumstances surrounding the behavior. It may be even more useful, however, to dispense with the concept of agency altogether in talking about shaping and focus on the shaping process itself.

Whenever shaping occurs, some response comes in contact with a reinforcer and the responses that follow adapt to the changing circumstances of reinforcement. It is a natural process between elements of an environment and not between agents and behavior. In this sense, all shaping is agentless.

Learn More

Take shaping and agency to the next level with important related concepts. Join Dr. Hank Schlinger for an in-depth look at reinforcement and verbal behavior in his courses, Critical Look at the Concept of Reinforcement and Reflections on VB at 60. And for clinical applications, check out Dr. Bill Ahearn’s course, Repetitive Behavior: Autism, Stereotypy, and Anxiety: Supporting Adaptive Behavior is the Answer.